Why Believing is Seeing: How Our Minds Shape Reality Through Meaning-Making

Exploring Metacognition and the Power of Beliefs in the Age of Information Overload

Have you ever caught yourself thinking that if people just knew more—if they were better informed—we'd solve many of humanity's problems?

Dogma, crime, prejudice, tyranny—all just byproducts of ignorance, right?

I used to believe that with the correct information, people would naturally become more rational and compassionate, and society would flourish.

This notion seems self-evident and is embedded in our narrative of progress: humanity evolving from ignorance to enlightenment by accumulating truths.

We imagine that as we gather more 'right information,' we progress until we finally solve our core problems and redeem ourselves by creating a techno-utopia.

We believed that the core problem of ignorance could be solved by information.

And then, the World Wide Web burst onto the scene—making the entirety of human knowledge accessible to anyone, anywhere, almost instantly.

Dreams of a techno-utopia filled our imagination and were shared by tech visionaries like Tim Berners-Lee, Bill Gates, and even Mark Zuckerberg.

Tim Berners-Lee envisioned the internet as a utopian platform breaking down barriers and providing universal access to information. He believed in this so deeply that he didn't patent the web, keeping it accessible for all.

Bill Gates thought that putting information at everyone's fingertips would naturally foster a more factual and rational world. He imagined people responsibly educating themselves, diving into scientific topics, and engaging in 'Socratic debates' online.

"The Internet is becoming the town square for the global village of tomorrow."

Bill Gates

Similarly, Mark Zuckerberg was convinced that connecting people would lead to positive change. He believed that 'by giving people the power to share, we're making the world more transparent,' assuming that more communication would naturally lead to a better, more understanding society.

The underlying assumption among these visionaries was explicit: That information can cure the ills of ignorance.

But here we are, decades later, and the reality hasn't matched the dream, has it?

Instead of technology connecting us to each other, informing us of clear truths and making society itself more enlightened it did the opposite. It divided us, it shattered the truth into a thousand small pieces and it drove us into a culture war.

So, what went wrong?

Why didn't the avalanche of accessible great information lead to the rational, compassionate society we envisioned?

Why are we more polarized and more entrenched in our beliefs despite the wealth of knowledge at our disposal?

It turns out that simply providing information isn't enough.

As Albert Einstein once said, "Information is not knowledge." And perhaps more importantly, knowledge isn't wisdom.

Today, we are quickly moving from a Techno-utopia to a Techno-dystopia.

The dream is becoming our nightmare.

Here is why.

Issue 1: Processing Information

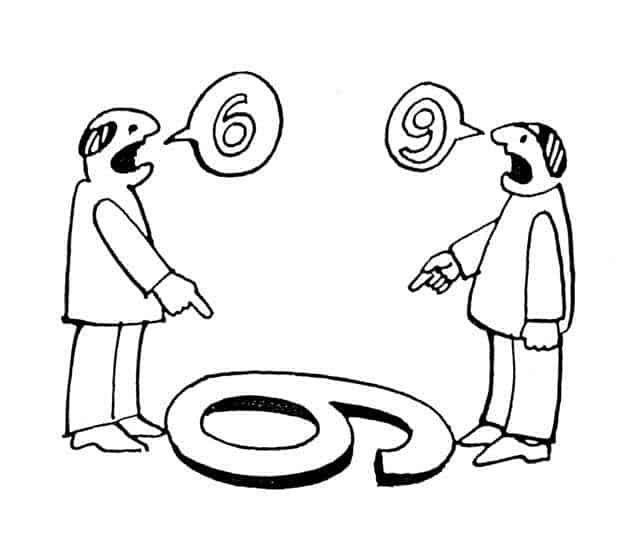

We assume that understanding the world is a deterministic process; that we see the world more or less as it is and that we all experience the same reality and the same set of facts.

We believe that information enters the mind like a jigsaw puzzle piece and that our minds solve the puzzle to reveal the overall picture.

But that is not how it works at all.

In reality, information is like water poured into a vessel. It takes the shape of the mind it enters, conforming to existing beliefs and biases.

Despite overwhelming scientific evidence, there are still groups of people who believe that the world is flat. They are provided with plenty of good, honest facts by society, but these facts have been warped by their biases to fit their preconceived notions.

Issue 2: Cognition vs Metacognition

This is the most fundamental issue.

We are so engrossed in our quest to understand the external world (cognition) that we overlook the need to understand our own thought processes (Metacognition).

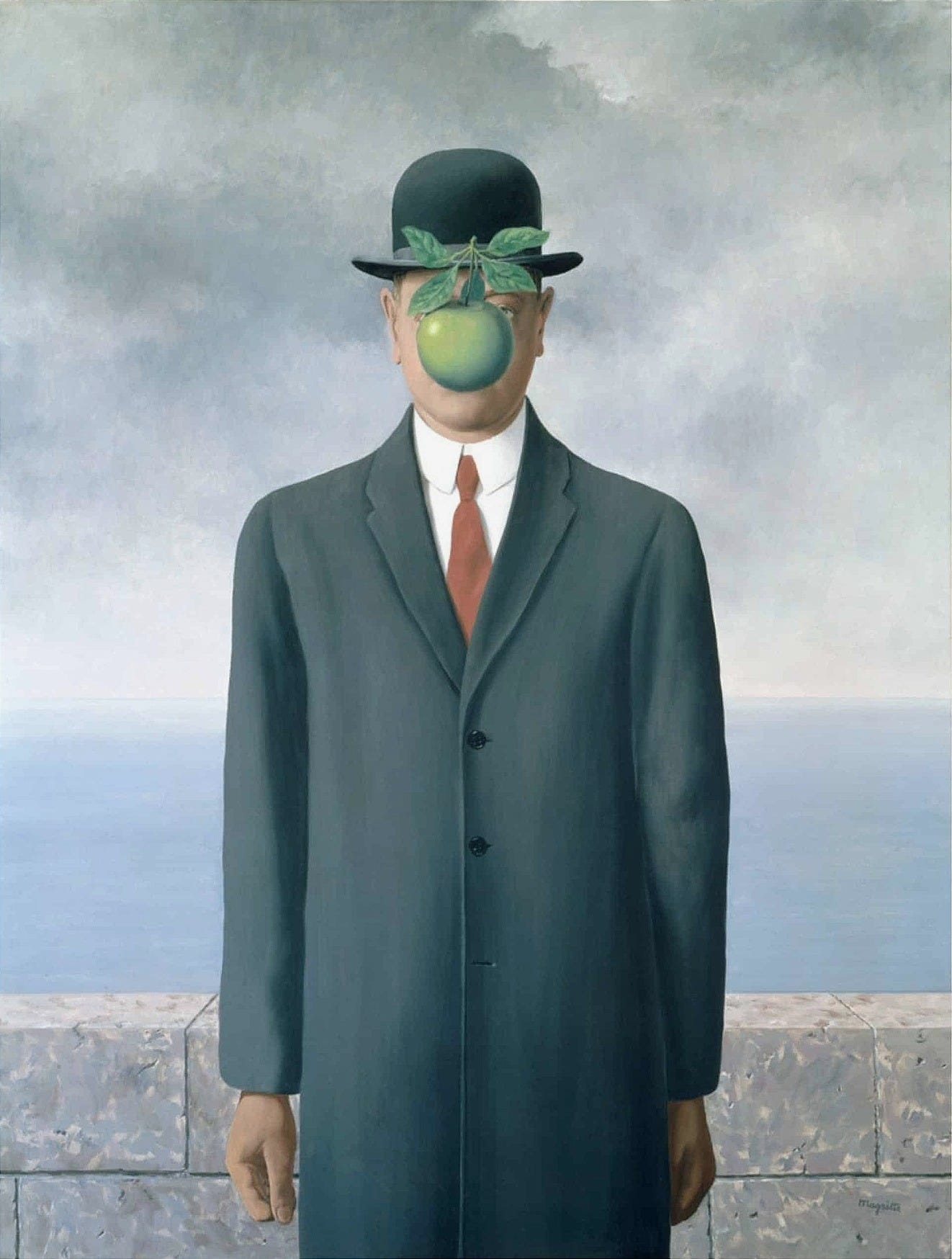

By failing to understand our own our own thought processes we don't understand understanding. As a result, we become susceptible to the mind's tricks — favoring pleasing illusions over uncomfortable truths, and distorting facts to fit our narratives.

It became evident that without Metacognition, all the thinking in the world would merely awaken us from one illusion only to entangle us in another.

Next, we will do a deep dive into how information is processed and cognized in each of us.

The Trinity: Subject, Object & Mean Making

We often only perceive reality through a type of duality, separating the subjective and objective world.

Baked into this view is the assumption that we, the subject perceive the objective world, more or less as it is, however this is not the full picture.

Why?

Because information is inherently meaningless.

I can tell you stories in Japanese, and you won't understand a word of it unless you know what the words mean.

So the subject/object is missing the component of meaning.

Thus, reality really is a Trinity of Subject, Object, and mean-making.

The Knower, The Knowing of Experience, The Known (object).

Now, let's dive into the Trinity, which reveals Metacognition at its highest level.

The Knower, The Knowing, and The Known

What is the Trinity of Experience? The Knower, the Knowing, and The Known.

Understanding the Trinity can take us to Metacognition and become self referral.

The 'Knower' is the subject of experience, the 'Known' is the object of experience, and the 'Knowing' is the meaning given to the experience.

The Knower gives meaning to the Known.

The meaning defines the relationship between the Knower and Known.

The Knower then experiences that relationship.

This is how we give birth to our world.

Reality is born out of a conscious subject giving meaning to their objective world and then experiencing that relationship.

This is our entire experience of the world.

This is, in fact, all we ever really know.

In this way, experience itself is our fundamental reality.

And this reality is consciousness… It always involves a conscious subject having an experience with information.

The experience with information, this mean-making is a relationship.

Our world, our entire life, is thus a set of relationships with meaning.

Now, let's look at how information is processed and how we give meaning to our world.

The Processes of Information

One evening, a Christian, an Atheist, and a Buddhist are hiking together. As night falls, they set up camp and gather around a crackling fire under a clear, star-filled sky.

Suddenly, they notice strange, shimmering lights dancing above the horizon—brilliant colors swirling and moving in patterns they've never seen before. The lights are silent, ethereal, and undeniably captivating.

They watch in awe as the phenomenon unfolds and take something different from the experience:

The Christian gazes at the lights and says, "This must be a sign from God—it's a reminder of His glory and presence in our lives." He feels inspired to pray, expressing gratitude and seeking deeper spiritual connection.

The Atheist, intrigued yet analytical, remarks, "This is fascinating! I have never seen anything like this, but there must be a scientific explanation—perhaps it's an unusual aurora caused by solar activity or a rare atmospheric event. Nature has many wonders we have yet to fully understand." He then decides to document the event, taking photos and notes, eager to research and learn more about the possible natural causes.

The Buddhist observes the lights and reflects, "The beauty of this moment lies not in understanding it, but in experiencing it fully."

How We Process Information

The story above illustrates the interplay between the know, the known, and the known. How we give meaning to our experiences and the interplay between meaning and beliefs.

Next, let's break down the process of processing information and giving it meaning. This includes 3 parts:

Attention

Perspective & Perception

Mean Making

Attention

In every moment there is way too much information and we don't have enough time to process all the information available to our senses, evaluate it and make sense of it.

Instead, we automatically filter the environment, and we focus our attention on what is important to us at the moment.

But this leaves us vulnerable and raises the question, if we focus our attention on a task like eating, how can we make sure that we don't get eaten?

The answer lies in the two types of attention and how they are associated with each of the brain's hemispheres:

The left hemisphere deals with the local, what is right in front of us, in the foreground.

The left hemisphere helps us to grasp and feed, move objects, and manipulate the world.

It reduces the world to what can be easily known, understood, grasped, and controlled.

Specialization: Focused Attention

The right hemisphere deals with the global picture – including the periphery and the background.

It is aware of the big picture and understands the broader context and relationship.

The right hemisphere, with its always-on context-aware global attention, ensures we do not become someone else's prey.

Specialization: Peripheral Attention

Our attention has both qualities, where we can focus on an object and are also aware of the broader view.

The broader background attention, constantly scans our environment for patterns that are in alignment with our system of values.

Survival and procreation are two examples of values that we have all experienced.

When we are hungry, we become ultra-attuned to notice foods we might want to eat. We can easily get enchanted with delicious smells and start imagining what we might want to eat.

When we are horny, we notice all of the beautiful people around us and grow in excitement. And when these needs and urges pass, we might not even notice the gorgeous woman of the smell of bread baking in the oven. The smell of food might even turn us off.

So, our attention is directed towards things we want and need, and this happens a-priori. As each new moment arises, our value system acts as a filter for our attention systems. Only after we are aware of 'the thing of value' can we move towards it.

As we move towards our goals, we focus and engage with what is valuable and helpful and ignore all of noise. The information that is meaningless, is not even registered by us. We won't be able to recall it accurately or might not even know of that it was there in front of us.

Surprisingly, this is the case even if we interact with a valuable object like money. Even here, we will only recall and focus on the most meaningful information, the part about money that gives money its meaning, and will leave the rest of the details behind.

Here below is an example of this phenomenon with a penny.

Even though we have seen thousands of pennies in our lives, the details of a penny are not meaningful enough to remember, so most of us can not identify the correct penny. Can you?

Perspective

As each of us perceives the objective world, we do so from a perspective. Our perspective is limited by time, space, our senses and our mind.

Thus, we never see the complete picture of any object of perception.

Instead, we see it as if it were frozen in time and space. We see it from a single point of view, which makes it appear to us in a very particular way that only tells a fraction of the story.

In this way, what we experience is the mean-making we attribute to the small amount of information we perceive.

Mean Making

After we focus our attention and the information begins flowing into our mind, our mind shapes it and gives it meaning based on an interplay of beliefs, experiences, and past meanings.

Consider how differently the Atheist, the Christian, and the Buddhist interpreted the dancing lights.

"The Christian gazes at the lights and says, 'This must be a sign from God—it's a reminder of His glory and presence in our lives.'… The Atheist… remarks, 'This is fascinating! … there must be a scientific explanation.'… The Buddhist observes the lights and reflects, 'The beauty of this moment lies not in understanding it, but in experiencing it fully.'"

Each of them gave the mysterious light a layer of meaning that was not directly a part of the experience. Instead, their beliefs about the experience and their model of reality gave the experience additional words that further shaped the experience.

Our beliefs, thoughts and words shape our actual experiences. We are then in relationship with our own projected meaning and imagination.

In this way, the meaning that our beliefs give to our experience is then reflected back to us through the dynamic relationships we have with our world.

Here we get a kernel of truth, which reverses the axiom 'seeing is believing' into 'believing is seeing'.

The belief shapes the interpretation of what is seen.

"The model we choose to use to understand something determines what we find."

― Iain McGilchrist

The Power of Beliefs & Values

Our beliefs and values literally shape the way we perceive the world and define our relationship with it.

We interpret the information in accordance with our beliefs and model of reality. Thus, the information itself is made to fit our values and perspectives.

This effect is so strong that scientific experiments, like drug testing, are double-blinded.

The first blind is designed to counter the power of beliefs, which manifests as the placebo effect. Here, participants are told that they could be receiving a sugar pill or the test drug. The purpose is that the participant will not know which one it is.

The second blind takes this a step further. To eliminate the opportunity of knowing, even the scientist that gives the drugs does not know if the participant is taking the test drug or a sugar pill. Without the second blind, the participants in the drug test could pick up on whatever information is there and this can skew the results!

Psychology Models & Beliefs

The power of beliefs is included in multiple psychological models such as the COM-B Model of behaviour and the PRIME Theory of motivation.

Motivation (Beliefs / Values) + Capability (Skills) + Opportunity (Environment) → Behavior

COM-B Model

The Models illustrate beliefs role in both perception and motivation. Beliefs shape perceptions, our relationship with the world and can then lead us to action.

In fact, beliefs and values are the building blocks of action. They provide the motivation to take action.

When we put it all together, Beliefs are like software programs.

They direct our attention and focus on what is valuable. They shape how we perceive the world and define our relationship with it. Then, they motivate us to take action and attain our wants and needs.

Conclusion

We often hear that seeing is believing, but perhaps the deeper truth is that believing is seeing. Our beliefs and values aren’t just passive filters; they actively construct the reality we experience. They shape our perceptions, color our interpretations, and guide our actions.

This understanding challenges the notion that more or better information is the remedy for ignorance.

In reality, additional information often gets assimilated into existing belief systems, reinforcing preconceived notions rather than dismantling them. At best, it might shift us from one illusion to another; plunge us from one dream into another.

So, the answer to ignorance isn’t simply more information.

Instead, it’s about becoming aware of the narratives we hold about ourselves and the world. It’s about recognizing the “dream” we’re living in and choosing to awaken from it.

![RockEDU on X: "We see pennies everyday, yet it isn't easy to select the right one. During our [LOL] on memory we asked students– Which is the real penny? https://t.co/ROonUwIjI8" / X RockEDU on X: "We see pennies everyday, yet it isn't easy to select the right one. During our [LOL] on memory we asked students– Which is the real penny? https://t.co/ROonUwIjI8" / X](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!VfRX!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd8c9ed8d-02c5-4b8f-8b97-b5c26e8f9963_974x1510.jpeg)